My last two outings on the Trans Swiss Trail were not my best days ever. First, the delays in the snow on Gräfimattstand completely disrupted my plans two weeks ago. And then last week, my walk was successful, but the rain took away from the enjoyment. But with good weather forecast last Sunday, I was resolved to go on with my adventure on the Trans Swiss Trail.

So it was that I set out early on Sunday and made my way to Stans. I had rained a lot during the night, and the streets were still wet as I made my way from the train station. My route too my up through the town, passing the basilica and the “Death and the Maiden” statue, heading out on the eastern road. Reaching the edge of town, I could see Oberdorf in the valley, and the mountains to the east still shrouded in grey clouds.

I went on down into Oberdorf. This part of the route still overlaps with the Jakobsweg, and I fully expected to see some interesting churches along the way. Of course, while the larger churches and even the basilica in Stans are all very interesting in their own way, but in many ways, I find the smaller churches more interesting. And in Oberdorf, there is a little gem, the St.-Heinrich-Kapelle.

The first mention of the church goes back to 1541, when there is a record in the bailiff’s book of a church built “for St. Battens and St. Heinrich”. In 1608, that older chapel was replaced. During the French invasion of Switzerland in 1798, the chapel was burned down, though it was rebuilt in 1801 based on the walls of the ruined building. Since 2014, it has been under the care of the Nidwalden canton.

The marble altar is decorated with a painting of the Madonna and child. There are also oil paintings on either side. On the right is Mary with Jesus, while on the left is Joseph with Jesus. The two saints, Beat, and Heinrich are represented in statues on each side of the altar. St. Heinrich, holding a model of a church is on the lest, while St. Beat, holding a book and a lance, is on the right. Further out from the altar are wooden statues of two local saintly men: Brother Klaus, or Niklaus von Flüeli, on the left and brother Konrad Scheuber on the right.

Leaving the little church behind, I went on, crossing the Unter Allmend stream and going up onto the ridge beyond. That soon brought me to the second wayside church of the day. Waltersberg is not even a village, more just a settlement of a few houses, but it is the site of the church of St. Anna.

This small church is richly decorated. An older church on the site was replaced in 1889 by the current structure dedicated to St. Anna. She must be one of the most overworked saints in the Catholic canon, being the patron saint of mothers, housewives, domestic servants, widows, the poor, workers, miners, weavers, tailors, hosiery makers, lace makers, farmhands, millers, grocers, boatmen, rope makers, carpenters, turners, and goldsmiths, not to mention having under her care the cities of Florence, Innsbruck, and Naples, as well as this little settlement at Waltersberg. She is also said to help find lost items, and to protect people in thunderstorms. She really has a lot to take care of. But aside from the altar decorations, the church is worth visiting for the high quality stained glass windows.

From Waltersberg, my route went down to the town of Buochs. Naturally, I could not pass by the church, but I found it large and uninviting, though well decorated. Somehow, it lacks the intimacy of the St.-Heinrich-Kapelle, or the artistry of St. Anna, Waltersberg. So I went out again, and just around the corner, I found a monument to the eighteenth century Swiss Artist, Johann Melchior Wyrsch.

Wyrsch was born in Buochs in 1732. As a young man, he studied art in Luzern, before going traveling in Italy. On his return to Switzerland in 1754, he worked as a professional portrait painter and church painter. But in 1758, he moved to Besancon in France. His work reflects the baroque and rococo styles of the time. In the 1780s, with his sight declining, we returned to Buochs, and set up a school of drawing. His eyesight continued to decline. But during the French invasion of Switzerland in 1798, he was killed by French troops. He continues to be remembered in the town of his birth and death.

Just a little further on, I came to the Kapelle of St Sebastien. Unfortunately, I don’t have much information about it.

After that, my route took me down to the lake shore. As I walked, the mountain tops were still covered in cloud, and it actually started to rain. It was not rain as I am used to, not even a drizzle, more just drops, not enough to really get wet, so I kept walking. Here and there, I could see walkers and cyclists stopping to put on their raingear.

But it wasn’t long before the trail left the lakeshore to go up to the Ridli Kapelle on the hill. This is not a tiny Kapelle, but it is a pilgrimage church, and part of the Jakobsweg.

And then, with the clouds lifting, my route went back down to the lake again. The clouds were still there, but the sun was winning and blue skies spreading above. I went on through the town of Beckenried, and along the shore. The residential areas go on for some distance, but eventually, the route enters a forest. By now the sun was out in earnest. I stopped for refreshments and the heavier clothes went back into the rucksack.

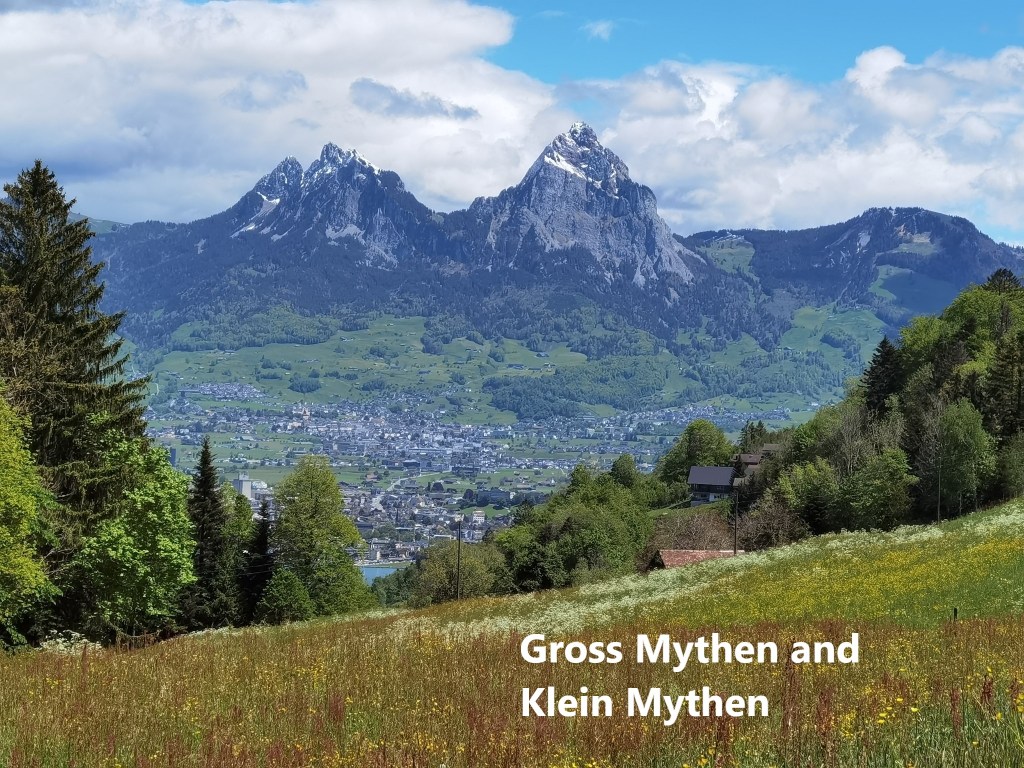

A little while into the forest, the trail turns away from the lake shore, and up the hill. It passes two impressive waterfalls and continues on up before turning again to resume the eastwards journey. At times, the path seemed to be following a narrow ledge between a rock wall on one side and a steep drop on the other. But eventually, the route flattened out into a forest trail before emerging higher up into fields and meadows. To the east, Gross Mythen and Klein Mythen dominate the landscape. Somewhere along the way, I crossed from Nidwalden canton into Uri. Originally called Uronia, the name of the canton was shortened to Uri sometime in the Middle Ages. The canton controlled the trade route over the Gotthard pass, and this was the source of much of the canton’s wealth, allowing it to behave almost independently, even when under Hapsburg rule in the thirteenth century.

The route went on and I came to Sonnenberg. I was surprised to find that what looked like a nineteenth century hotel is now the Maharishi European Research University. The very name brought me back to the 1970s, when the Maharishi and the practice of yoga burst on the world scene. The message from the Maharishi about peace, inner well-being, and general love for all mankind and the world was a convincing one, linked to the practice of yoga and meditation. But when it was noticed that the Maharishi wore Rolex watches, it emerged that his mission to benefit the world came at a cost to his followers, and material benefit to himself. I have learned to find my meditation and well-being from my hiking in the outdoors, so I took no interest in the “University” in Sonnenberg and went on, soon reaching Seelisberg.

From Seelisberg, the route starts to descend. Seelisberg itself is almost directly above Rütli, the place where in 1291, the leaders of the three cantons Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden swore the Rütlischwur, or Rütli oath, pledging common defence for any canton attached by their larger imperial neighbours to the north. It began the process of building the coalition of cantons that is modern Switzerland. I would have liked to visit Rütli, but it was unfortunately just a little too far off my route in terms of descending all that way, and then back up again. So instead, I continued the descent. Passing the Marienhöhe shrine.

Every country has its formation legends they are not limited to the older, welll established nations. From the legends surrounding Clovis, first king of the Franks in 496, through Robin Hood in medieval Britain, to the legendary invincibility of El Cid in chasing the moors from Spain, events take on a mythic quality as the centuries pass, and Switzerland is no exception. it is not known what format the Rütlischwur took back in 1291, or even what date it happened. But in reality, that doesn’t matter. The fact is that it happened in some shape or form. William Tell was present around the same time, and how much of his story is reality is another question. But the two sets of events, of the Rütlischwur and William Tell’s exploits have served to create a legend, not of invincibility, but of resistance to the invader. Invincibility was sadly absent when Napoleon invaded in 1798, but resistance was definitely there. And that is perhaps why, even in a Europe generally at peace in the 21st century, the legends live on.

It was a gradual descent, and easy to follow, through forest initially, and then past fields of grazing cows, all the way to Bauen. Bauen itself is a small village, sandwiched between the mountains and the lake. Because of its situation, it has a special microclimate, and some of the vegetation looks sub-tropical. It is a picturesque place, and a good place to finish my walking for the day.

I had time for a refreshing beer before going to the jetty to take the boat to bring me to the train station. I was lucky enough to make the schedule for the Unterwalden, a paddle steamer of historic vintage. She was built in 1901, but her engine was on display at an International Exhibition in Paris, so she did not take to the water until 1902. She was converted from coal firing to oil in 1949, which is why no vast plumes of black smoke come from her funnels as she travels. In the 1970s, when progress was the order of the day, there were moves to have her retired, but after a campaign by loyal enthusiasts, the decision was taken to retain the vessel and she was completely renovated in the early 1980s. She got another overhaul in 2008 and continues to work the lake to this day. It was a privilege to go out on such a ship as the Unterwalden, even if it was only to cross the lake to the nearest train station.

That train station was Flüelen, and from there I got the train back to Basel, my day’s walking done.

And the total step count for the day was 50,489.